Tom Evers - Storied Places

/Tom Evers, Executive Director of Minneapolis Parks Foundation at Water Works in Minneapolis. Photo: Tracy Nordstrom

Fourteen bridges span the Mississippi River within Minneapolis: Camden connects North to Northeast; Father Louis Hennepin connects downtown to old St. Anthony; Ford connects Minneapolis to St. Paul. Each crossing ties neighborhood to neighborhood, links history of place to modern day pursuits, and traverses a grand, moving body of water the Dakota call Haha Wakpa that is, at once, hugely culturally significant, and intensely personal.

Tom Evers is easily this city’s fifteenth bridge.

His compact build belies the expansive goals Tom has set for himself and the non-profit Minneapolis Parks Foundation (MPF), which he leads. “We are here to elevate our park system to meet the needs of our constituents,” he says, sounding official. His animated, frequently smiling face – with its boyish sprinkling of freckles and a cinnamon-and-sugar beard – communicates something even more elemental and innate: parks are where the fun is. To Tom, who is both a “big kid” at heart and a big thinker, fun is only half the power of parks; the compelling remainder lies in a park’s ability to heal a city, and the people who call it home.

Tom Evers addressing stakeholders at Water Works on the Minneapolis river front. Photo: Tracy Nordstrom

Tom discovered the fun of parks, as many of us did, when he was a kid. “Growing up on a cul-de-sac” in his hometown of Mankato, Tom says, “my childhood was full of free play down at the river and in the woods.” In addition to nature access and a freedom to roam, Tom found the structured world of play at the local playground “wonderful” for making friends and keeping busy, and it sparked in him a love of programmed public places. He remembers: “the neighborhood park had two staff people who organized games and art for us. It was all we did; we couldn’t go anywhere else. The park staff filled the space with fun and play, and the kids came together.”

Kids and staff enjoy Minneapolis Parks. Photo: Minneapolis Parks Foundation

Tom might have been a lawyer when he grew up, but he could not shake the promise of parks to satisfy his needs for adventure and community belonging. “I don’t know what I would have done as a kid without Mankato Parks,” he says convincingly. Succumbing to the pull, Tom spent the early years of his career as a Park Ranger in Vermont, and physically building public trails; he advocated for play and the merits of outdoor recess for children; he then raised funds for public land acquisition and conservation.

Across job and location, Tom embraced the serious, hard work of building parks without losing sight of the joy and possibility of public places: “I love what parks require us to decide, to plan,” he says. “I love the commitment of folks working on parks and important public places.” Place, he asserts, is where the essence of community resides, and what connects us across difference and time. Tom’s curiosity compels him still. He posits: “Place holds stories that are ready to be unlocked.”

Since 2003, the Minneapolis Parks Foundation has raised $22 million in private funds to enhance and support Minneapolis’ award-winning public park system, with $18 million of that to complete a contiguous “River First” linear connection - with greenspace, park amenities, and programming - along both sides of the Mississippi River (11 miles of shoreline total). Maintenance of the existing park system (established in 1883, and now including 6800 acres, 180 separate park locations, 55 miles of biking and walking paths, 11 lakes, and over 400,000 public trees) consumes the bulk of the MPRB’s general fund obtained from taxes; the Foundation adds resources and opportunity, and big thinking, to a system that has set the standard for public parks for 129 years.

Haha Wakpa, or The Mississippi River, runs through Minneapolis. Photo: Minneapolis Parks Foundation

The Minneapolis Park Foundation aligns philanthropic dollars with a broad community vision. MPF provides funds and direction for new projects and an ever-expanding park usership. “The community has big ideas but not big money,” says Tom, who has led the Foundation since 2014. And while big donors and corporate dollars are important contributors, Tom says fund-raising and planning efforts are “broad invitations” that intentionally include the “next generation of park users.” “As we think about our riverfront,” he suggests, “let’s create a story big enough that more people see themselves here. Let’s make it accessible so people believe it is possible.”

Water Works is a signature project the Minneapolis Parks Foundation has launched to animate a more inclusive story of people living and working here. Water Works is one of numerous sites along the city’s upper riverfront that are being purchased, re-imagined, or re-designed to better connect Minneapolitans to the flowing water, to the past, and to each other. As the water moves, so does our mindset: “We are a different city than we were 30 years ago,” Tom acknowledges. It is hard not to consider the political divisiveness and recent social unrest as we contemplate the city’s challenges. Our public processes and places, Tom notes, “have to solve different things for different populations.”

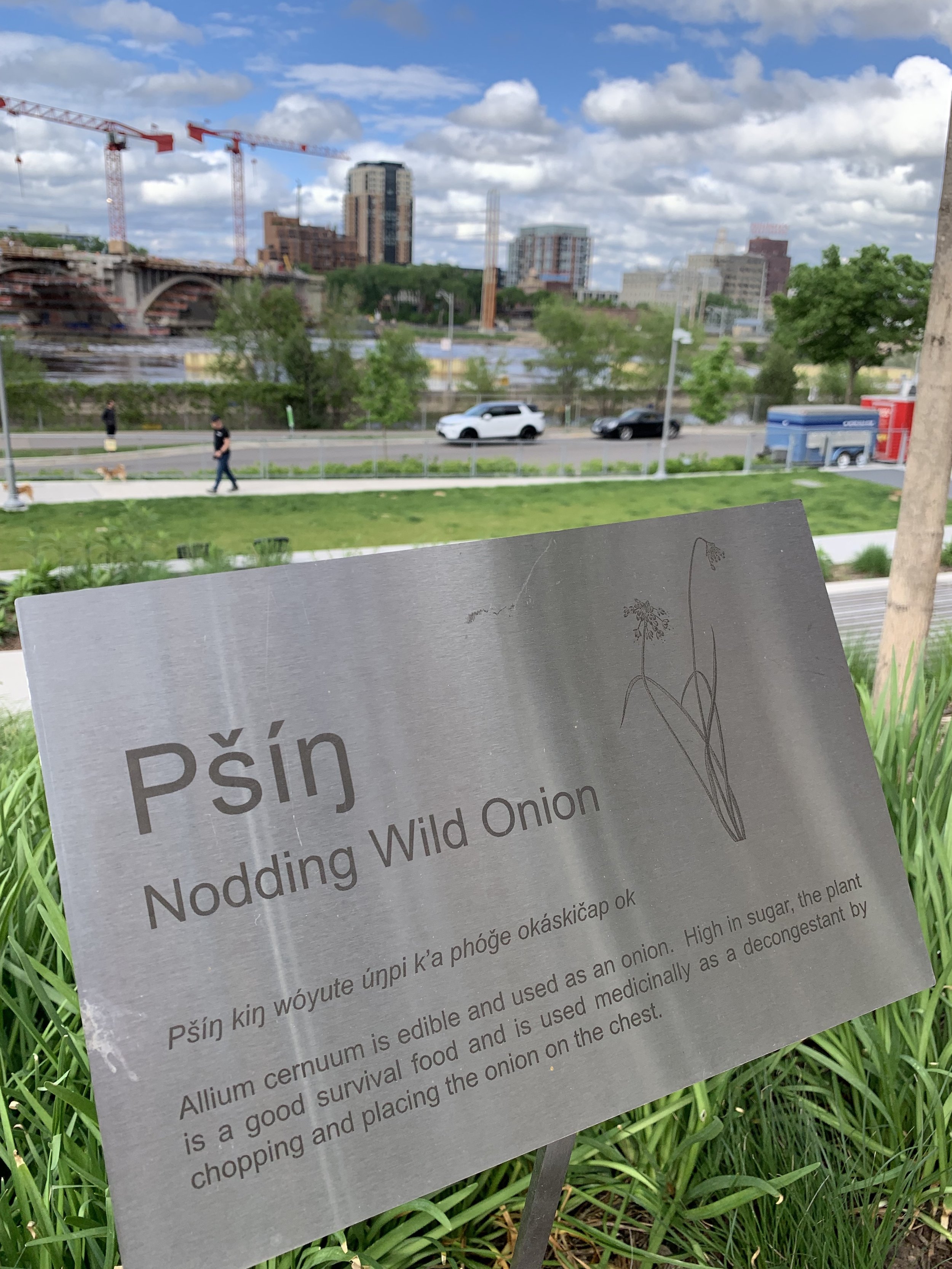

The newly opened Water Works offers a physical space to bring people together: it includes a public terrace, hillside seating and grassy “stage” area for performances, a nature-themed playground, a re-furbished mill building with public, non-gendered restrooms, a wudu station for ablution, reservable meeting spaces, a signature restaurant, outdoor tables, native plantings, lawn games, fire pits, and strings of lights to add energy and ambiance.

With stone ruins of its gritty milling past still visible across the space, the re-imagined Water Works offers a narrative beyond the mythos of 19th century white male industrialists and the “taming” of the mighty river. Tom describes how the MPF shaped public engagement in early 2016 planning for Water Works, and some of the stories that might be interpreted there. He says:

We engaged over a hundred individuals and groups in our planning. We knew we could not just have memorial plaques or a museum commemorating everyone who is important to this place

Consider the story of Reiko Weston [female owner of Fuji Ya, Minneapolis’ first Japanese restaurant which operated on the site from 1968-1990], who bought rail land here, wanted a connection to water, brought in a Japanese architect, and who envisioned people moving back into the once industrial area

There is the story of Amos Yancy: born into slavery, freed, he worked in this building when it was the Bassett Mill. He was one of the few African Americans working and living here at the time. He lived HERE. How do we tell that story? [Or of] the Pullman Porters who worked the rails into Minneapolis?

Or the millennium of Native people who were here first?

This physical space is a crossroads. For each person, there are different stories to tell

Sean Sherman (Ogalala Lakota) and Dana Thompson (Wahpeton-Sisseton, Mdewakanton Dakota) are now telling their story through their all-Indigenous restaurant, Owamni. Owamni is the heart of Water Works and has been bustling since opening in 2021 (reservations are highly coveted and hard to procure). “Sean [‘The Sioux Chef’ and James Beard award winner] showed up with an idea we didn’t even know we needed,” Tom says. The restaurant’s early success demonstrates how hungry Minneapolitans are for better history, better food, and better representation in our parks.

The name Owamni comes from the Dakota word, Owamniyomni, meaning “place of turbulent, falling water.” It is the original name for what is known in English as St. Anthony Falls. For thousands of years, Owamniyomni was a gathering space for Dakota, Ojibwe, and Ho-Chunk people, and holds a spiritual significance. “The river was here before,” says Tom, thinking about layers of history. “Connecting to water is what Water Works is all about. Owamni helps us connect with stories that have been missing at this location, Indigenous stories.” And, he emphasizes, “Food is a connector.” The neon sign hanging at the front door of Owamni is a potent opening line for this new chapter and reads: “You Are On Native Land.”

Owamni, at Water Works. Photo: Tracy Nordstrom

Tom knows that hosting one restaurant serving Indigenous food or commemorating an early Black pioneer will not correct the “under-telling” of stories or re-animate all the spirits of this place. Creating the physical space is a foundational step, and programming showcasing underrepresented voices will be vital (on Water Works’ docket for summer, 2022: Twin Cities Black Film Festival; Tatanka food truck; Women Singing Songs of the Diaspora from Jewish and Eastern European roots). “We haven’t fully oriented ourselves yet,” Tom offers as he reflects on Minneapolis’ ability to ACT on, rather than just refer to, our most recent racial reckoning. “Water Works,” he says, is trying to be “really intentional” by creating a welcoming space for more residents and visitors to “see” themselves here; to participate in public joy; and to see and be seen by others.

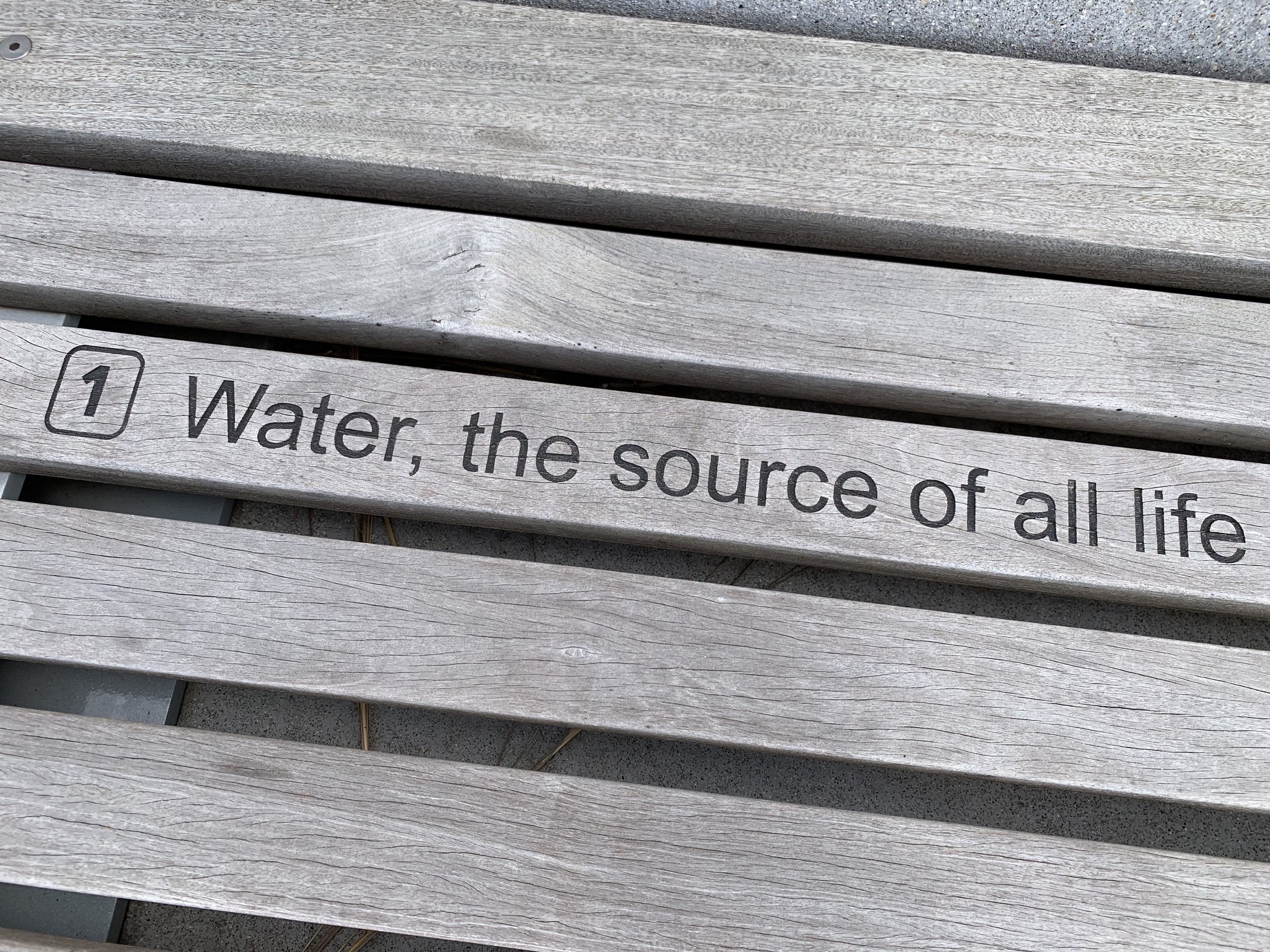

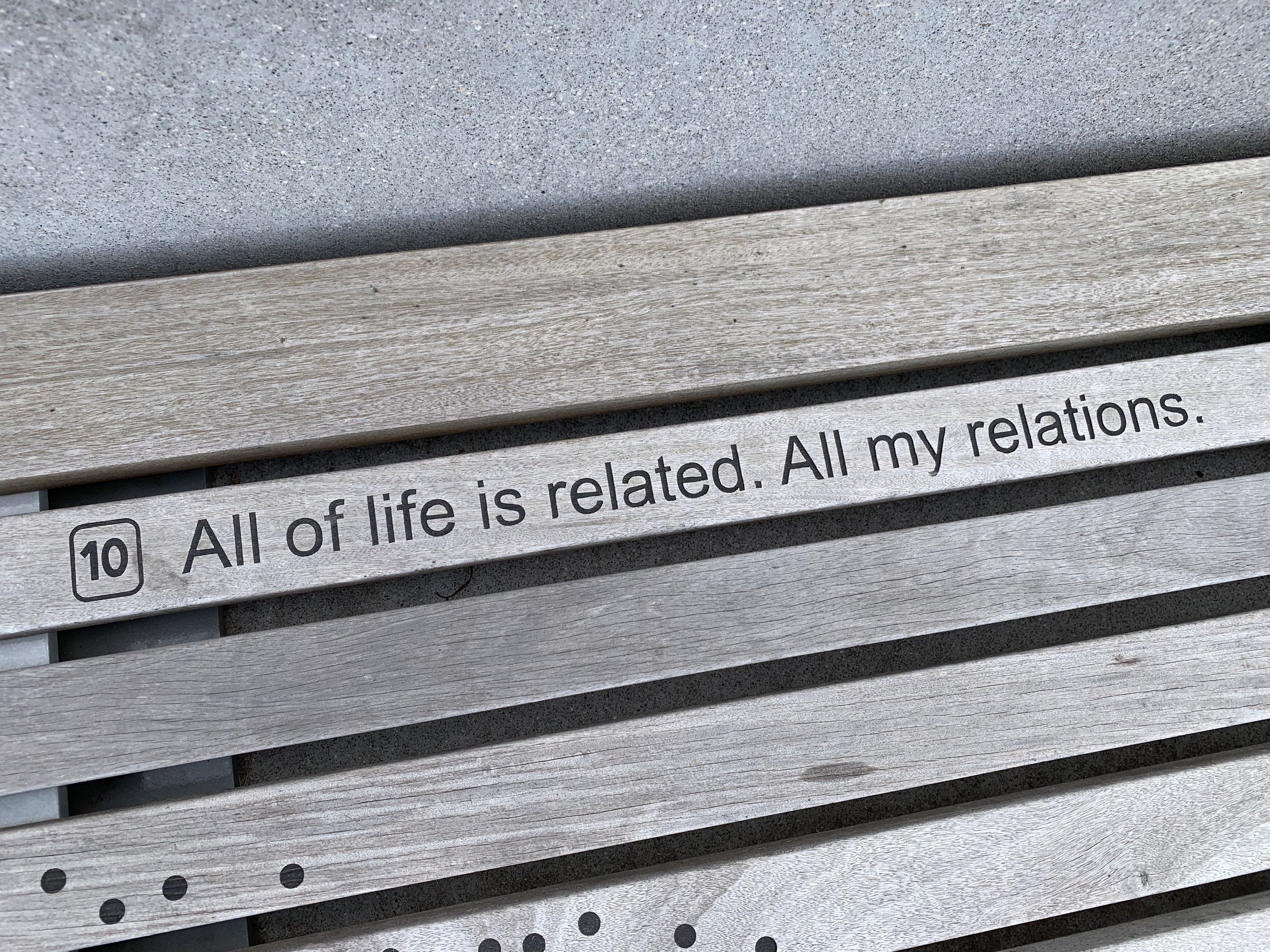

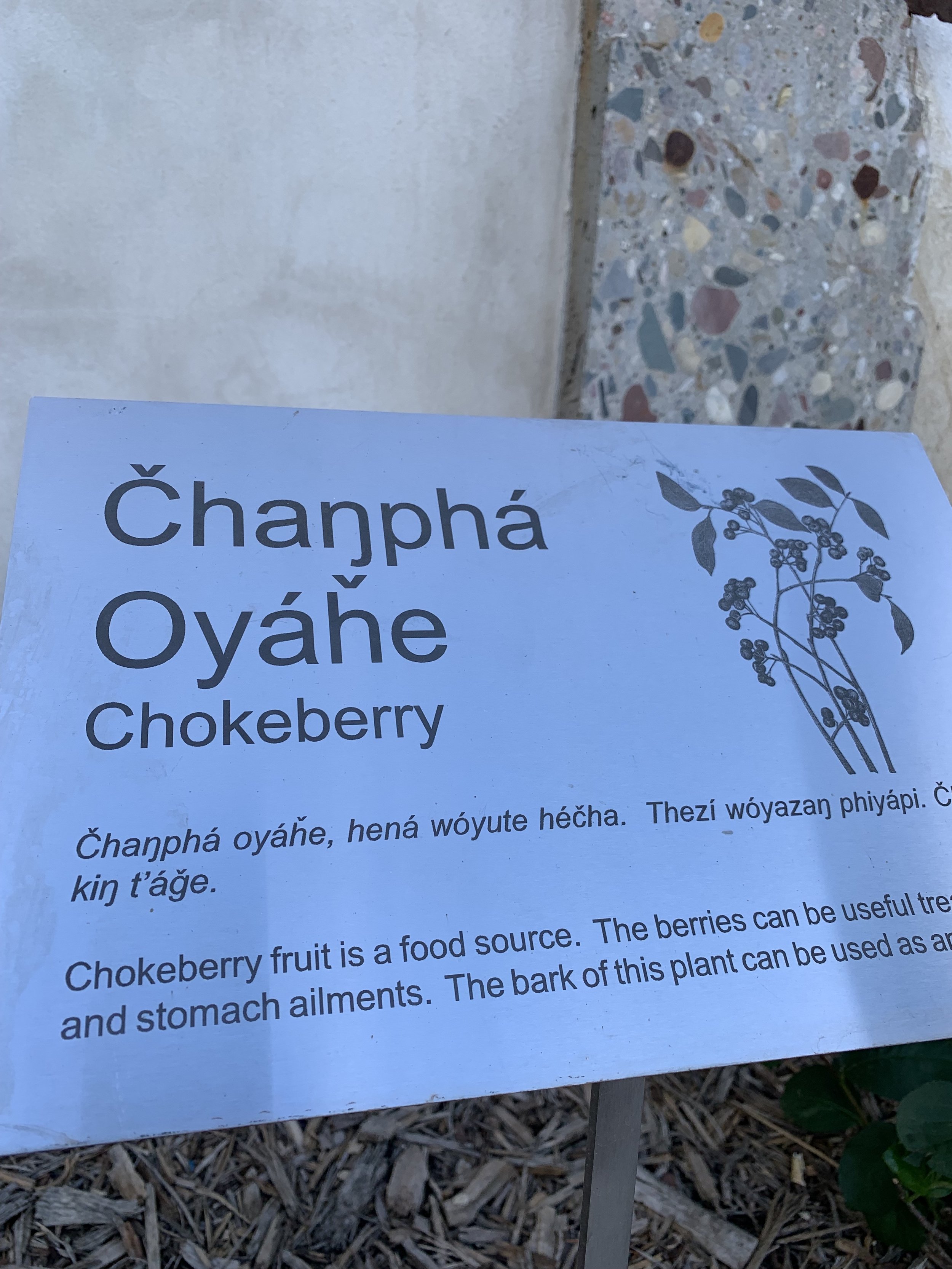

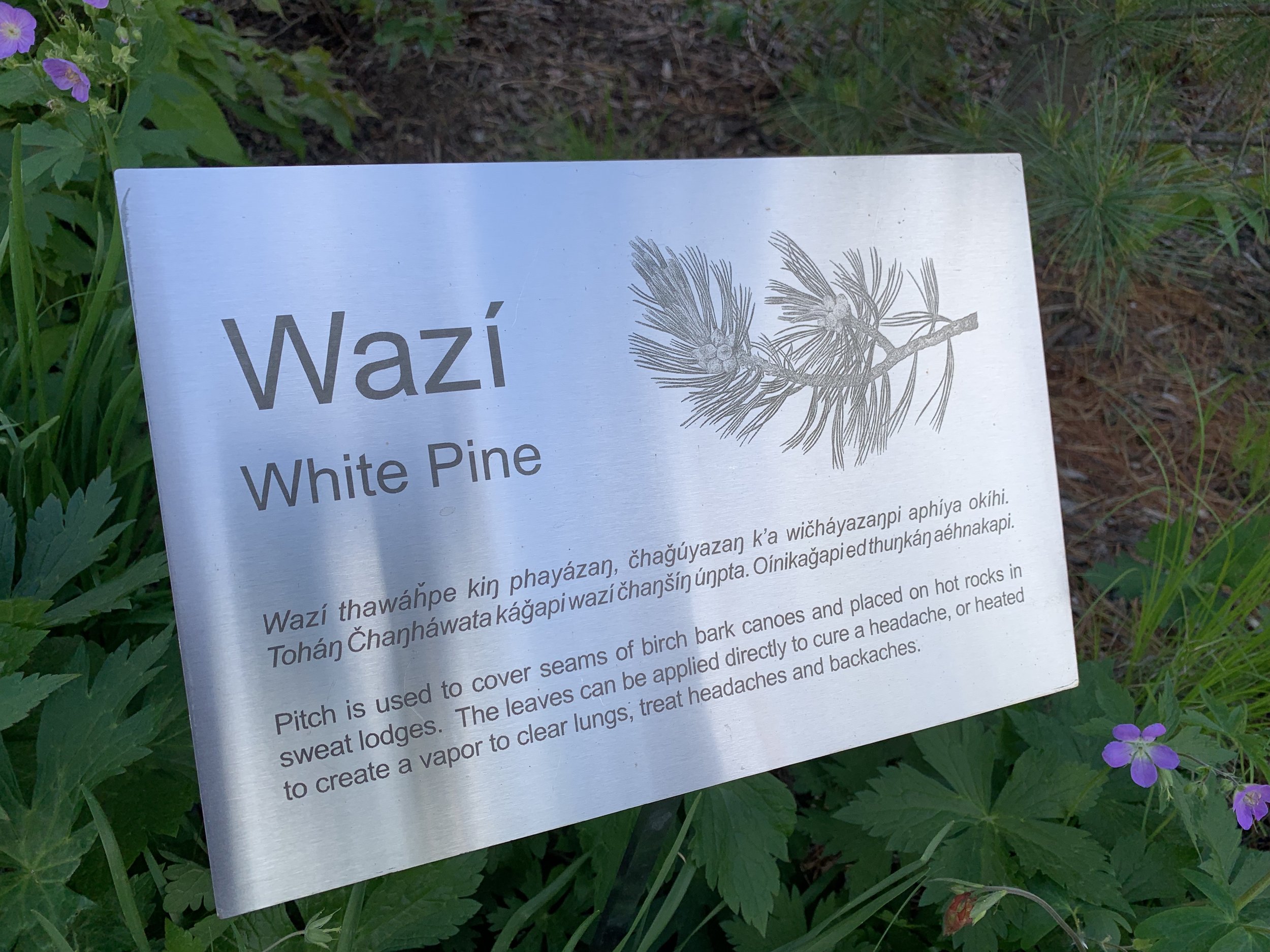

Looking at the visitors on this evening - late May, the river is rushing with spring melt, and puffy clouds are sliding by overhead – Tom says: “You can hear it.” He points to the people sitting and playing on Water Works’ steps and terraces: “Multiple languages.” Visitors, indeed, are milling about talking among themselves, to their children, and even to dogs on leashes in Hmong, Spanish, English, Somali, and what sounds like Russian or Ukrainian. The menu at Owamni pairs Dakota with English, as do the outside benches and plant signage. “I really see storytelling as the backbone” of our parks and the Minneapolis Parks Foundation, Tom affirms. “We’ve been given the opportunity to think big, and we need to do that.”

Kids connecting on the new playground at Water Works. Photo: Tracy Nordstrom

Resources:

Minneapolis Parks Foundation: https://mplsparksfoundation.org/

Water Works: https://www.minneapolisparks.org/parks__destinations/parks__lakes/water-works-at-mill-ruins-park/

MPRB Site Plans and PowerPoint presentation on Water Works: https://www.minneapolisparks.org/_asset/b7tge6/water_works_open_houses_concept_design.pdf

Owamni: https://owamni.com/

Interview with Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson of Owamni: https://www.kare11.com/article/money/business/behind-the-business/owamni-is-now-open/89-b49494f0-ff4a-465a-be8f-ec045c367434

Photos by Tracy Nordstrom, Minneapolis Parks Foundation & MPRB. Image of Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson at Water Works by Minneapolis-St. Paul Magazine.