Mary Lyons - Water Protector

/Mary Lyons - Photo: Jane Feldman. Tee shirt designer Votan Henriquez, NSRGNTS

As a Water Protector, Great Grandmother Mary Lyons (Leech Lake Ojibwe) is never very far from the element she stewards.

On this day, Mary is in a car with her granddaughters driving from the Atlantic Ocean west across Florida to the Gulf Coast. She crosses the state near Lake Wekiva, the most recent body of water in the US to be granted legal rights. Mary celebrates the victory for the Sunshine State as she passes through. The car windows are down, and her girls are singing and laughing. Mary sounds gleeful, glad to be on vacation with this giddy group; she knows her work is not done.

Mary has been celebrating and protecting water for over 50 years. “Water carries memory,” she says. “Think about it: For nine months you are afloat in water in your mother. We enter the world through water.” Growing up, water surrounded Mary in northern Minnesota: Lake Winnibigoshish and Leech Lake are where she played as a child, where her father and uncle fished, and where wild rice grows.

Wild rice harvest on Leech Lake

Minnesota is called the “Land of 10,000 Lakes” (there are actually 11,842 lakes that are at least 10 acres in size), and the state’s name comes from the Dakota phrase, “Mni Sota Makoce” which means “land where the waters reflect the sky.” The shoreline around those lakes equals 44,926 miles, longer than the coast of California. Including the shores of Minnesota’s rivers (both sides) would add another 69,200 miles (https://bit.ly/2PfXycg).

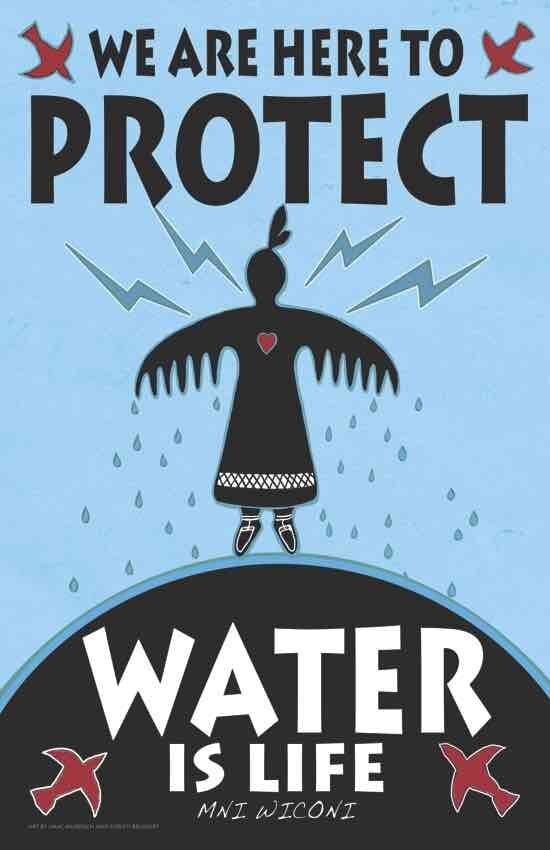

In places like Minnesota and South Dakota, the Water Protectors –activists, mainly women, many Indigenous- bring attention to corporate misuse of resources around water; defend Indigenous treaty rights; build advocacy; and change laws to grant rights to bodies of water, like the voters of Orange County in Florida did, with 87% of residents voting to grant Lake Wekiva and its watershed the “right to exist, flow, to be protected against pollution, and to maintain a healthy ecosystem” (https://bit.ly/2PAO2jU).

Mary Lyons with her daughter, grand daughters, great grand daughter and Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo)

Mary has traveled the world to safeguard waterways and the people who rely on that water for physical and spiritual life. She celebrated with her Maori relatives in 2017 when the Whanganui River received legal rights. Mary traveled then with other Grandmothers (Water Protectors from multiple countries) to New Zealand. The Whanganui River on New Zealand’s North Island became the first body of water in the world to be granted its own legal identity, with “the rights, duties and liabilities of a legal person.” The Maori people fought for that recognition for over 150 years.

Since then, India, Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, and several Sovereign Nations in the US have granted bodies of water “Rights of Nature” to protect them against pollution and neglect; Bangladesh has granted all of its rivers legal rights. Closer to home, Minnesota’s White Earth Band of Ojibwe legalized the Rights of Manoomin, or wild rice, in 2018. According to the press release, wild rice was recognized because “it has become necessary to provide a legal basis to protect wild rice and fresh water resources as part of our primary treaty foods for future generations” (https://bit.ly/3u6gOba).

Recently, Mary has been a frequent protestor and supporter of Water Rights along Enbridge’s proposed pipeline route in northern Minnesota, drawing attention to the threat oil production, transport, and spills carry for local water resources and Indigenous tribal lands. As a Great Grandmother, she recognizes that global climate change is the result of many generations failing to care for water and the planet. “Mother Earth is feeling the strain and the pain,” she says. “She brings in the tsunami, the hurricane, snow, ice and fog” with greater frequency and power to show her displeasure.

While protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline in South Dakota in 2016, Mary says Mother Earth heard the prayers of the Water Protectors after they clashed with local law enforcement: “At Standing Rock, all the spiritual leaders were there, and the Water Protectors were getting hit hard. They called in the vets. The elders could see things from the Ancestors, and we asked the Creator for help. A storm came. Blinding. The prayer was intense. We were asking to protect the Water Protectors.”

Mary is a study in contrasts: mighty and serious about her work to expand water rights around the globe; and her lightness and ebullience draws other grandmothers and great grandmothers (and young women and celebrities!) to the cause. She is often on the front lines with a raised fist, her signature beaded, floral-design hat, a colorful ribbon skirt, and a broad smile. She is as comfortable around a bonfire as she is presenting to the United Nations. She has a melodic laugh, bright eyes which take it all in, and waggish sense of humor. This great grandmother might know her actual age (she divulges that her great-granddaughter is 10 years old), but she’s not letting on. “I was assigned an age when I was little,” she teases. “But I was given my brother’s age!” Her younger brother, she adds laughing, “And I’m sticking to it!”

For all her work around the world, Mary notes that bodies of water in her own backyard, the Twin Cities, haven’t been given the deference or protection they deserve. “New Yorkers are working on protecting the Hudson,” she offers, “We need to push for the Mississippi to have rights.” For now, she is focused on protecting the headwaters of the Mississippi in the place that is her childhood and Anishinaabe homeland. Indefatigable, and looking firmly toward the future, Mary faces her Water Protector work with joy: “Every morning I thank the Creator. I hope that what I do throughout the day honors my ancestors, makes them smile. Healing comes through water. When water is healthy, your spirit can soar!”

Photo by Glen Stubbe, Star Tribune

Resources:

Photographs: from Mary Lyons’ Facebook page, unless otherwise noted

Mary Lyons, Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mary.lyons1

Mary Lyons, Wisdom Lessons: Spirited Guidance from an Ojibwe Great-Grandmother https://birchbarkbooks.com/all-online-titles/wisdom-lessons

Honor the Earth: https://www.honorearth.org/welcome_water_protectors