Mr. Marvin Roger Anderson - Reconnecting Rondo

/Mr. Marvin Roger Anderson embodies the honorific “Mister.”

As a prominent elder in St Paul (Morehouse College graduate; attorney; retired MN State Law Librarian; alumnus of the Improved Benevolent Protective Order of the Elks of the World; community organizer, historian, and cultural curator), Mr. Anderson has earned the title of respect. More importantly, he is a Son of Rondo. Rondo is the neighborhood of his birth; it is a place imbued with dignity where “we always referred to the men and women as Mr. and Mrs.”

As a Son of Rondo, Mr. Anderson has become an activist and organizer to pay tribute to his community’s past. His chronicling also anticipates a resilient future.

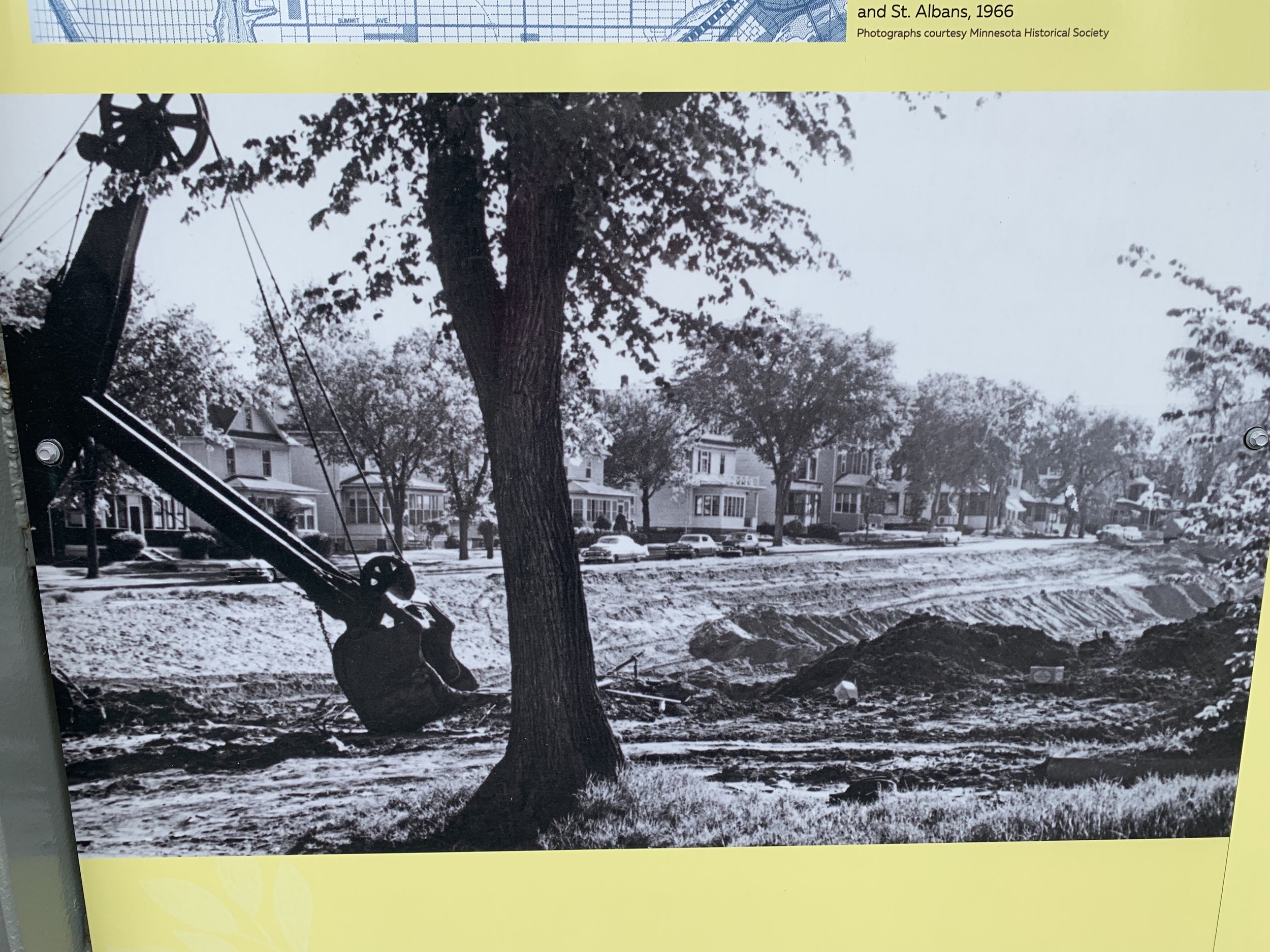

Rondo had been a predominantly Black neighborhood, tight-knit and thriving, before the trench for Interstate 94 divided its geography in the 1960’s. In the 1930’s and 40’s, 85% of St. Paul’s Black residents, both working- and middle-class, lived in Rondo. More than 600 families lost their homes and businesses because of the freeway’s construction; vibrancy, wholeness, and sense of place was lost, as well.

To remember Rondo’s history and to highlight its on-going resilience, Mr. Anderson has co-founded and champions a three-fold community restoration: Rondo Days (an annual event), the Rondo Commemorative Plaza (a place), and ReConnect Rondo (a vision). As a placemaker, Mr. Anderson covers all bases. For almost 4 decades, he has been building bridges between generations of Rondo Sons and Daughters and across racial divides; in the case of ReConnect Rondo, he plans to build an actual bridge to suture a physical and spiritual gash that divided Rondo decades ago.

On this Day, Mr. Anderson talks about his work at the intersection of Concordia Avenue (“Old Rondo”) and Fisk Street. Bees are busy collecting nectar from boulevard plantings, and the midday highway hums below. There is a formality, a crispness to Mr. Anderson that indicates he is both a “man about town” and that he means business. He cuts a striking figure at the Rondo Commemorative Plaza: hip, dark blue jeans, an impeccably pressed denim shirt, a light-colored sport coat appropriate for a warmer-than-average autumn afternoon. His sartorial seriousness is leavened by an easy smile and playful, multi-colored striped socks peaking over polished loafers. He hosts the energy of a teenager.

As he describes the origin of Rondo Days, an annual neighborhood celebration since 1983, Rondo’s historic exuberance lights up his brain. He channels the chatter of the Black barber shops, BBQ restaurants, social clubs, grocery stores, and churches that once flourished from “The Hill” of Rondo to “Cornmeal Valley.” His verbal recollections vibrate with the ideas he and his neighborhood buddy, Floyd Smaller Jr, riffed on in early planning sessions.

“We created this whole structure,” Mr. Anderson says enthusiastically, “with meetings and committees. Rondo Days would have it all: a parade with a marching band; the American Legion drill team; the Elks; sororities; a softball team called Uncle Shirley’s Old Timers; the Boy Scouts; a boat; a drum and bugle corps.” There would be music, a fashion show, a play about Rondo, and an Ecumenical Sunday church service with choirs, even an oratorio. Mr. Smaller and Mr. Anderson organized publicity, sanitation, first aid, transportation for dignitaries, security, a photographer, and a collection of photos.

The inaugural event had great appeal, Mr. Anderson recalls, because people in Rondo needed it. “There was a malaise, there was an untapped need to coalesce again.” Everyone with a connection to Rondo wanted to participate; so much so that in the first year, “hardly anybody was there to WATCH the parade because there were 500 people IN the parade!”

Mr. Smaller and Mr. Anderson have been the driving force behind Rondo Days for 38 years. An integrated community comes together each summer to remember and to make new memories. “Over the years,” Mr. Anderson observes, “we have built up momentum and an identity and an awareness. We are at the point where it can go on its own.”

Now Mr. Anderson, retired from paid work, focuses on a physical space, a year-round celebration of Rondo; a place for reflection, storytelling, art, and community gathering. “I thought to myself, ‘Let’s fashion a way for people to tell these memories before they are lost’,” he says. “We need something permanent. I imagine this Plaza to be part of a larger, nation-wide network of plazas, memorials, and historic sites commemorating communities that lost what once existed. It will be part of a new ‘Green Book’, a new way of marking places,” Mr. Anderson posits, referring to the Negro Motorist Green Book (first published in 1936 by Harlem postal worker, Victor Hugo Green) that once led traveling African Americans to hotels and eateries that were welcoming to them during the dangerous segregation of Jim Crow.

In 2018, the Rondo Commemorative Plaza opened at 820 Concordia Avenue as “the nation’s first public memorial dedicated to a community destroyed by public action.” St. Paul’s first Black mayor, Melvin Carter III (a Son of Rondo whose parents lost property when the freeway came) attended and proclaimed July 14 “Rondo Commemorative Plaza Day.” Minnesota’s then-Commissioner of the Department of Transportation, Charlie Zelle, also attended the Plaza opening. Mr. Zelle formally apologized to attendees on behalf of the State of Minnesota for the construction of Interstate 94: Bisecting Rondo was “something [that] should never have happened,” he said. “We’ve learned our lessons. It’s not about just the past, it’s about where we are now and how to go forward.” Hundreds of Sons and Daughters of Rondo celebrated the plaza’s opening. Acknowledging a new diversity in Rondo, representatives from the Somali, Hmong, Karen, and Oromo communities also spoke at the event.

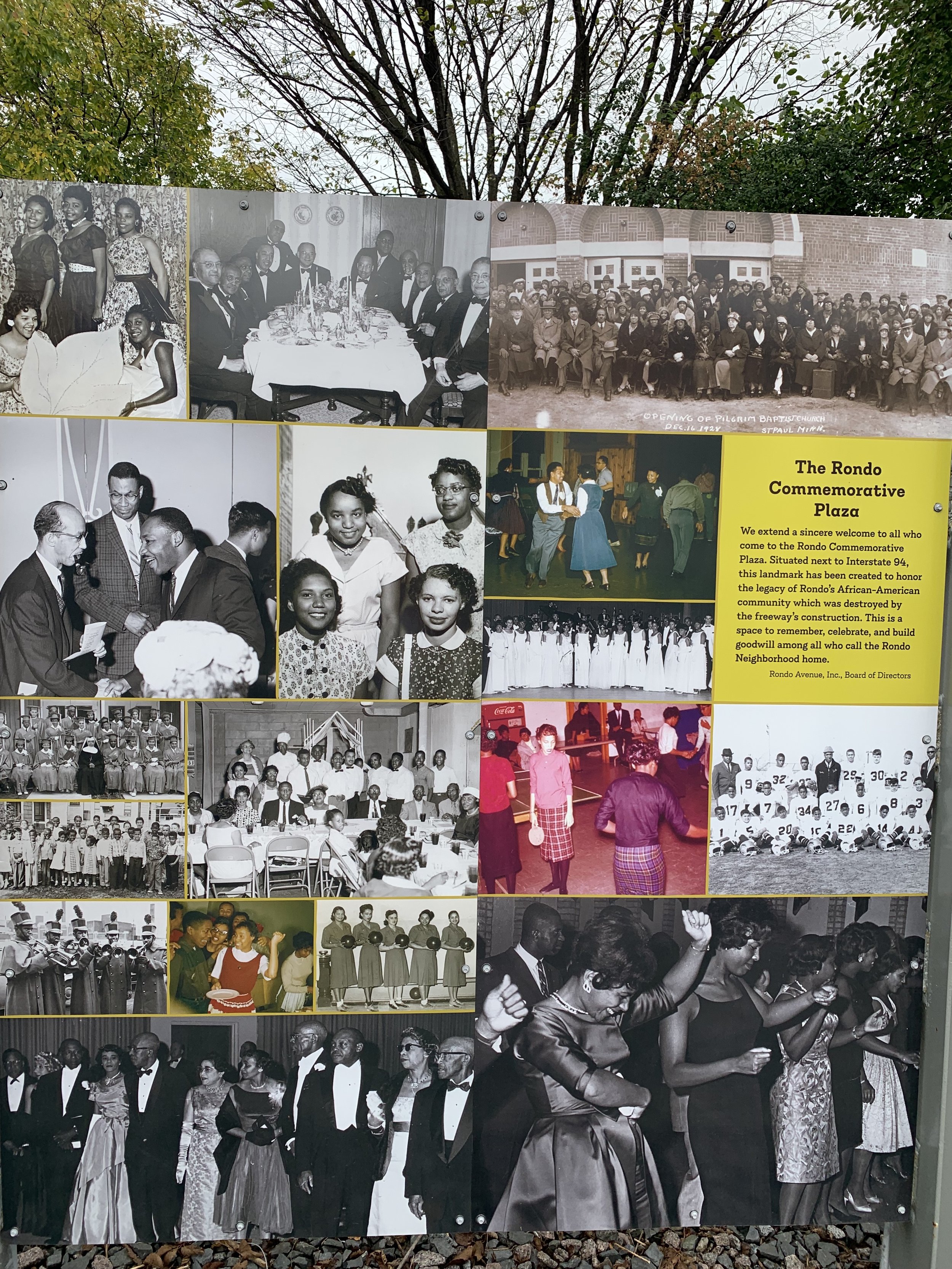

Rondo Commemorative Plaza. Photo: 4RM + ULA

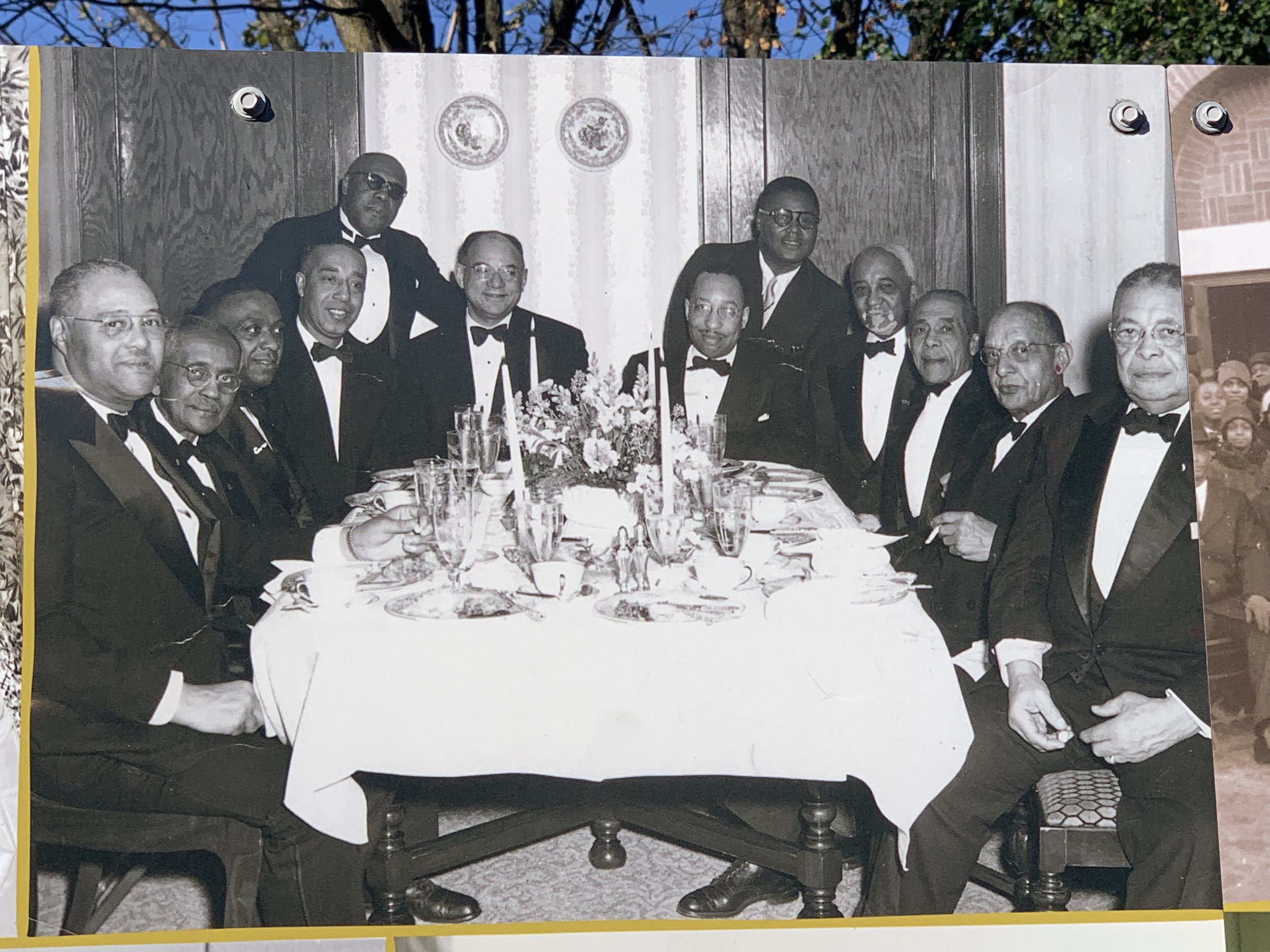

The Commemorative Plaza is flanked by 14 colorful panels that interpret the history of Rondo with photos, text, quotations, and documents. The public Plaza contains pollinator gardens, a pergola, potted blooming plants, seating, a lush lawn, and a tall marker proclaiming “Rondo” surrounded by young trees. There are photos of Rondo’s once-thriving businesses, neighborhood leadership, and social organizations. One panel lists homeowners’ names and the addresses of properties taken via eminent domain for the freeway’s construction.

Describing the Rondo of his youth, Mr. Anderson testifies: “We had social, economic and political power. Remember,” he continues, “there was disenfranchisement, dislocation, discrimination, and a devaluation of Rondo [by the dominant white culture in St. Paul]. This plaza celebrates the resilience of our community. Here are the stories; we are passing the baton to our youth. We are looking to the future from right here.”

Sitting in a small building adjacent to the outdoor Plaza (recently purchased by the Rondo Center of Diverse Expression), Mr. Anderson enumerates how the building will augment programming in an indoor facility, with climate control and bathrooms. He moves about the open space with alacrity; he has a chair for this interview, but mostly he is on his feet, gliding as his thoughts lead him. He waves his right arm in an arc: “This will be where we show films by Black filmmakers.” A collection of articles and books about Rondo and written by Black authors are in piles on makeshift shelves. He then waves his arm over his left shoulder: “And this is where we will have an archive, accessible to everyone in-person and on-line, a ‘history harvest’ of neighborhood artifacts and household items that tell the fuller story of Rondo.”

When asked how he maintains such buoyancy decades after devastation and beneath the weight of inter-generational trauma in the Black community, Mr. Anderson takes a deep breath and settles in. He begins: “I have an exceptional group of elders around me. Their philosophy was and is, ‘Don’t curse the darkness, light a candle!’ I am determined. I will have to show you. This is about layers,” he says, listing the community accomplishments: “First, Rondo Days; then the park when we got money for the Plaza; and now we are going to re-connect Rondo with a land bridge.”

Artist rendering of Rondo Land Bridge, over Interstate 94, St. Paul MN

He acknowledges that he needs an assistant, and a part-time librarian to catalog the full history of collected images, artifacts, and stories. But the accumulation of items and the acceleration of big ideas, if cluttered, are not slowing him down. This past July, the MN Legislature approved $6.2 million dollars to study and plan the “capping” of Interstate 94 the length of three or more city blocks to stitch together the bifurcated Rondo. The vision is to create an African American Enterprise District that could include housing, business development, public art, and community spaces on top of the freeway. “We recognize the damage it has done,” he says, pointing in the direction of the freeway’s open trench. “Now we must change it.”

Earth movers digging the I 94 trench in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood, circa 1960

Rondo’s untold stories compel him. “I am an elder,” he says, “all of this is in me. I have to get it out of me!” He reveals a memory of his childhood, describing his personal roots, a communal hardship weathered, and illustrating one story from the universe of stories of Rondo that need to be told and captured before the elders pass:

“My grandfather was a Pullman Porter, and my dad was a railroad waiter. The Pullman Porters were all called ‘George,’ to dehumanize them, keep them down. The waiters were also not called by their proper names, but were called by numbers, Number 2, or Number 1. That was an attempt to show us as not-human, as interchangeable pieces of property, to take away any vestige of respect or common courtesy. If they [white folk] would go so far in one direction, we [in Rondo] went the other, building each other up. We called them “Mr.” and “Mrs.” in community. Always with respect, with dignity. When we got back to Rondo, we were somebody. “

There is a lot to do yet in, and for, Rondo, to honor those important “somebodies.” The next steps (the building, the archive, the land bridge) will connect the memories of Rondo’s older generation with the imagination of the young. Mr. Anderson wants every day to feel like a family reunion in Rondo, full of hope and music, familiar faces, and possibility. There is a physical and cultural ecosystem to re-establish, and re-invent. “If you don’t know your history,” this dignified and dedicated Son of Rondo offers, “then you don’t know your future.”

St. Paul’s Pullman Porters

Resources:

Reconnect Rondo: https://reconnectrondo.com/vision/history/

St. Paul History of Rondo: https://saintpaulhistorical.com/items/show/160

Rondo Days: https://www.rondodays.net/

Rondo Land Bridge: https://www.twincities.com/2021/07/01/rondo-land-bridge

Rondo Center of Diverse Expression: https://rcodemn.org/

Photos: Tracy Nordstrom, Minnesota Historical Society, Rondo Avenue Inc. (unless otherwise noted)