Bruce Chamberlain - Iteration in Design

/Bruce Chamberlain appreciates deep roots and the elements that nourish them.

From his farm boy days, the land, and the people who tend it, have shaped him. When his parents chose to go organic for their dairy production, Bruce noticed big and small changes, saying, “Animal health improved, smells evolved, insects returned. Roots grew, and a more complex ecosystem emerged.”

Observations like that inform his current work as a landscape architect and thought leader. The city of Minneapolis is Bruce’s home now, where he focuses on the creation of - and investment in - public spaces. As Bruce tells it, good public spaces contain “layers of functionality: ecological, social, aesthetic, economic, historic.” Place begins at a physical, ground level: “Soil is the richest ecology we have on earth,” he offers. From there, Bruce leans into metaphor: teaming with variety and life, the soil’s complexity and its “organic nature mirrors the way cities become special places.”

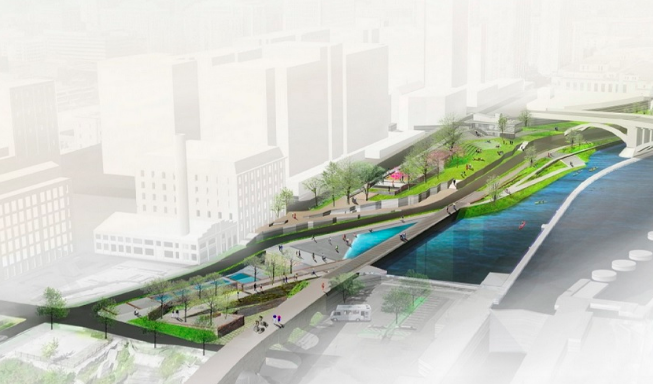

Drawings for Fuji Ya site and downtown riverfront

The built environment, particularly the public parks, drew Bruce to Minneapolis. During his years in private practice and his tenure as Assistant Superintendent for Planning at the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB), Bruce noticed the impact that the 135-year-old public park system has had in shaping the character of this “special place” and the people who live here. He notes:

This city, more than any city in America, is framed around its park system. The linear concept of green (around waterways, extending through parkways and boulevards in each neighborhood) is fundamental. Our parkway system is a framework for the city, and an ethos for conservation and connectivity. That cadence of parkway / front yard / front door is carried throughout the city. That sets the pattern that development is predicated on public space.

Today, Bruce serves as Parks Fellow for the Minneapolis Parks Foundation (a non-profit fundraiser for the Minneapolis Parks) and principal designer at his firm, Loam (a term that describes a soil type ideal for growth). In each role, Bruce says his goal is to create a “pathway from vision to implementation” by “marrying lofty goals to action.” He is interested in equity opportunities, strengthening environmental integrity, and building partnerships throughout the city and surrounding communities. He consults on both public sector projects and broad “initiatives.”

Bruce pauses to distinguish “project” from “initiative”: “Sheridan Park is a project,” he instructs, “RiverFirst is an initiative.” Sheridan Memorial Park (1300 Water Street NE), with its public art (the lit spherical shield sculpture by Minneapolis artist Robert Smart), gardens, veterans’ memorials, and river views is a park with familiar amenities and is grounded in a physical space. RiverFirst, is described as an idea, a promise, a vision and process; a wide-ranging plan to transform the Mississippi River as it runs through Minneapolis into a “21st Century treasure, accessible and relevant to all.” In describing the urgency of this work, Bruce stresses the river’s cultural, historic, environmental and economic significance, and the connections and opportunities it provides people. Bruce offers: “We turned our back on the river. It is time to return it to our front yard.”

Hall’s Island restoration - part of RiverFirst initiative

This “front facing” aesthetic runs through Bruce’s work. His interest is connecting people to both “natural and social resources” and correcting “equity injustices” by “building and providing amenities in areas that haven’t historically had them.” Current projects include the Water Works, in downtown Minneapolis, and the Upper Harbor Terminal in North Minneapolis. Both projects promise to connect citizens to the Mississippi River by providing access to the water, recreation, trails, and restored native areas. The designs for improvements will reflect community needs and be influenced by those who will use them. The hope is that improvements will bring people to the river’s edge and fish, birds, and other wildlife back to healthy and sustainable levels.

As Parks Fellow, Bruce is also charged with guiding the Next Generation of Parks lecture series and inviting the public to weigh in on deficits and opportunities in our parks. In his thought leadership, Bruce starts by building relationships with people who will affect, and be affected by, a public space. He asks a lot of questions: “How do we invite [the broad public] so the process is meaningful and engaging?” “How do we get stakeholders into the room and at the table?” “How do we ensure agency?” “What are the shared values here?” and “Are we trying to get something built, or are we building community?”

That community piece is integral, as balancing broad challenges and goals is complicated. Bruce notes that, at one time, public agencies could more easily build where and when they liked, but today, public/private partnerships are required to sift through complexity, catalyze a range of funding sources, and arrive at something wonderful. “Government used to have a lot of power, agencies could get things done,” he says. “By the 1990’s, government resources really declined, tools diminished, and partnerships took on more importance. Government cannot do it alone.”

With Bruce’s guidance, public agencies, private clients, and conservancies (those emerging public/private entities) can leverage private sector funding to build and maintain public sector projects. Describing Loam’s recent work with the City of Excelsior, for example, Bruce describes his advisory role and how a city’s capacity, and stakeholder involvement, can grow:

Excelsior is a legacy landholder [of a public space] and they are charged with caring for it, investing in it, paying for it. The city provides a basic standard of care – they apply city resources to mowing and tree care. But there is not enough money to keep it the way the city’s stakeholders want it, and there are not enough public funds to invest in improvements. There is a layer between the city and [private fund] philanthropy; that is the conservancy model. [For me,] that is the sweet spot, the placemaking role, and [I tell them – stakeholders and elected officials], you can have agency.

The conservancy model is not everyone’s cup of tea, and often there are significant challenges. Bruce is undeterred: “My new work is to develop new strategies, to turn vision into implementation. Some things can be easy to accomplish – like putting a sculpture or playground into a certain space. Others are hard, like Mill Ruins Park [along the downtown Minneapolis waterfront] where there is history, contaminated soils, a hyper-engaged constituency, and uncertainty.” In these cases, learning as you go, listening and layering solutions matters: “One plan is not enough,” Bruce says, “Iteration is key.”

Shield sculpture at Sheridan Memorial Park in Minneapolis

For more information:

https://mplsparksfoundation.org/riverfirst/

https://www.mwmo.org/projects/halls-island-scherer-site/

Photo credits: Minneapolis Parks Foundation, RiverFirst, Mississippi River Watershed Organization, Greg Lundgren Photography