MaryLynn Pulscher - Nature Play!

/“I’m a ‘Say yes, let’s see what the possibilities are,’ type of person,” says MaryLynn Pulscher, Environmental Education Manager at the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. She’s a risk pusher, too, given parental focus on a “Be careful, don’t get hurt” ethos so prevalent these days.

In the Minneapolis park system, MaryLynn seeks a different set of play parameters. “When I was a kid, we built forts, we played in the swamp,” she says. Much of her play was creative, inventive, and collaborative with other kids up for an adventure. “Kids should be outside every day,” she offers, “Doing their own problem solving, building things.”

Not that there is anything wrong with pre-fab play structures or organized sports, but there is something special about kid-play that is open ended and invites freedom to “work together to lift a log, balance sticks, or construct an imaginary ‘hot lava’ river they can navigate only if they stay on the tree cookies they hop along.”

Nature play, or outdoor adventure play, is not a new concept. Since the beginning of time, children have roamed freely outdoors (saber tooth tigers notwithstanding), fording streams; collecting rocks and flowers; engineering sand castles with elaborate moats; capturing and studying caterpillars, toads or tiny snakes; and climbing trees and over and under fallen logs. Why? Because it’s fun, and a little dangerous, and, until recently, there weren’t other distractions keeping kids indoors.

In today’s world, where parents are strapped for time and many children are tethered to electronic devices, outdoor play is often allotted in limited, highly regulated chunks. Recess at many schools occurs only on blacktop, within school boundaries, on immobile equipment, and only if the weather is good. Some schools have reduced or removed recess altogether as officials pursue higher test scores and more time spent at desks on prescribed learning.

This “on task” track might benefit from some “off trail” time, suggests MaryLynn. Author Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods (2006), warned of a “Nature Deficit Disorder” rising within the wired generation. Research provided by The North American Association for Environmental Education explains that outdoor, active and unstructured play leads to multiple health and societal benefits, including:

· Reduced rates of childhood obesity;

· Predictability of active adulthoods;

· Greater creativity and better concentration;

· More inter-gender play than on equipment-focused play;

· Decrease in attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder;

· Strengthened immune systems in children due to plant, animal and soil exposure;

· Development of life-long conservation values and stewardship.

MaryLynn sees cost benefits as well. Providing natural elements – logs, sticks, sand, hay bales, swaths of fabric, string, water – is cheaper and readily available in local park systems and provides easier access for neighborhood groups and users. As an example, MaryLynn offers: “We have created a Nature Ninja Play concept outside at the Kroening Nature Center in North Minneapolis that combines monkey bars with stumps and obstacles for jumping over and on. People pay up to $18 an hour for indoor ninja play. This one is free!”

The imagination that MaryLynn developed while nature playing as a kid is still wildly with her. “ [The] Forestry [Department] flinches when they see me coming,” she demurs as she describes the many ideas she has for re-purposing and re-imagining everyday “park waste” like logs from damaged or removed trees. “I have this big idea for a huge oak tree,” she says. “The foresters are unbelievably good sports. They can make it happen.”

MaryLynn fashioned a pop-up pilot nature play area a few years ago adjacent to a structured playground space at Nokomis Park, just north of the busy lake and along the popular bike and walking trails. The nature play space is still going strong, and each day the assemblage of materials appears in a form different from the day before.

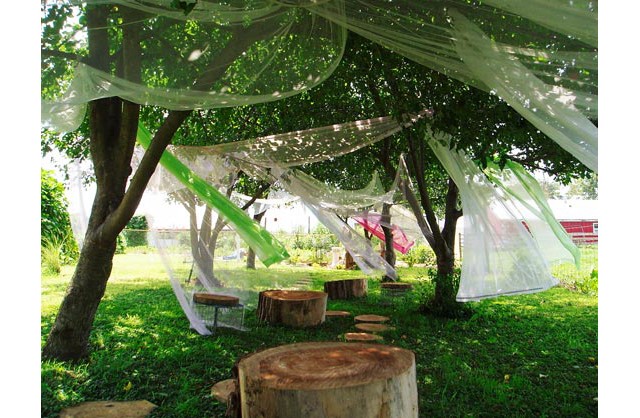

At the space, MaryLynn had Teen Team Works, a job training program run within the Minneapolis Park system, cut logs crosswise into disk-shaped “tree cookies,” strip long tree branches of leaves and smooth them, and stack them in piles for kids to “co-architect” once play begins. The site also includes hay bales, a large evergreen tree with low branches for climbing, and one huge log on its side, drill pressed with holes and outfitted with tiny wooden pegs for use as a giant cribbage board (or gang plank!).

There are guidelines that assure safety, however fun and “dangerous” the free nature play is meant to be. “We consider risk management,” MaryLynn asserts. “Public parks carry recreational immunity, and we have standards for tree parts, limits to tree heights where we think kids will climb, and we provide sticks that are long and heavy enough for building teepees, but not short or light enough to be used as swords.”

Feedback for the pilot nature play area at Nokomis has been encouraging. MaryLynn installed a sign at the site with a “Tell us what you think” email address and phone number. One parent offered: “We were here for 4 hours today. Here is what my kids built (pictures attached): a pirate ship, a spaceship, a submarine and different forts.” Routinely, parents put their phones down and join in the play. “Bigs and littles, side by side!” MaryLynn beams. “Data suggests parents might join in for about 15 minutes on pre-fab playground structures, but up to two hours” in a nature play.

In May of 2016, MaryLynn showed off her nature play pilot at the national conference for Children in Nature Network held in St. Paul. By then, the movement was gaining steam across North America. She joined Canadian landscape architect Adam Bienenstock, a “Disruptive Designer” of nature play areas, and led a bus full of rule-busting grown ups from St. Paul’s River Center to Lake Nokomis in the rain.

For over an hour, the assembled park planners, community organizers, and environmental advocates tried out the natural play elements and watched a cohort of local preschoolers navigate the elements in their rain boots and brightly colored slickers.

MaryLynn and Adam credited the “awesome power of nature” that contributed to fun, health, and teamwork in play. Adam called to mind a scene that MaryLynn understood well. He directed participants: “Close your eyes. Call to mind the smells, sounds and stories from your own magical, outdoor play spaces of childhood. Did they make you feel adventurous? Powerful? Creative? Those feelings,” he said, “- and that natural space - carried you through childhood and, if you are lucky, inform the person that you are today.”