Nathan Campeau - Water that Once Was

/Nathan Campeau, water engineer. Photo: Tracy Nordstrom

Bassett Creek; Phalen Creek: Bridal Veil Creek: Cascade Creek.

These names are like secret hydrological codes in Minneapolis and St. Paul. Water engineer, Nathan Campeau, is a super sleuth: he is knowledgeable about where the water that once-was-above-ground is now, and he’s focused on where it’s going.

A surface portion of Bassett Creek in Minneapolis. Photo: Bassett Creek Watershed Management Organization

There are other creeks and waterways, too, that once crisscrossed the topography of the Twin Cities, but their names have been lost from memory, erased from maps and, like the creeks themselves, pushed deep underground.

Turns out, the Twin Cities was (still is!) a watery place, and as human habitation densified and expanded in the 19th and 20th centuries, civil engineers drained local wetlands and put many of the area’s creeks into tubes or tunnels underground, creating dry, flat ground for rail lines, houses, roads, and other elements of the built environment that became the city (or two). “Humans have always been drawn to water,” Nathan says, “for trade, for sustenance, for crops. What we have done over the past 150 years in the Twin Cities is bury our valuable water resources.”

Sanitation was one imperative: the flush of moving water was an initial solution for human waste but became a health hazard as more people lived in closer confines and shared the resource. A photo of St. Paul’s Swede Hollow (circa 1910) shows an outhouse perched precariously over Lower Phalen Creek, the same creek that provided water for washing and recreation for locals. When the City of St. Paul built a sanitary sewer system to manage waste, nearby surface waterways were also wrangled underground, easing development, mitigating seasonal flooding, and further reducing risk of disease. “Some of these waterways were open sewers,” Nathan acknowledges. “They were not to be celebrated but avoided.”

Outhouse in Swede Hollow, St. Paul, on Phalen Creek (circa 1910)

Nathan’s fascination with water began early, in junior high science class: “Growing up in Minnesota, constantly around water, my formative experience was taking samples at Coon Creek, testing for water quality and hunting for invertebrates.” By college, he cultivated other interests. “I thought I would be a diplomat or politician,” Nathan remembers, “and then I realized that I was more excited by the technical side of the challenges that confront us.”

Now a Vice President and Water Resources Engineer at Barr Engineering, Nathan is focused on water as a resource to revere, not just relocate. “I started out in flood control, flood mitigation,” he says about his initiation into the profession. “When I discovered what ‘green infrastructure’ was, about 15 years ago, I realized how critical this work is.” Green infrastructure uses plantings, wetlands, and natural features to mimic the water cycle rather than muscling the water out of the way or into mechanized water treatment facilities.

That epiphany, and the industry’s evolution, has changed how cities think about water. With the right planning, Nathan says, “our city can function hydrologically like we are treading lightly. Like the built environment isn’t even here!”

That built environment fascinates Nathan. Because of his job, and his everyday curiosity, he knows a lot about the tunnels and tubes that convey our cities’ water. “Every time I run by something,” Nathan, an avid jogger, admits: “I wonder: What was that? If it’s not being used, where did it go?”

In the many hours he spends underground for work, Nathan sees evidence of wildlife that has stayed close to water (raccoons, ducks, fox), and the evidence of humans, too. “There is lots of evidence of humans in those tunnels,” he says. “Graffiti, some artful, some not; and poetry. I’ve seen Ode to Trout Brook. Beautiful!” There is a subterranean speakeasy in Minneapolis, too, but Nathan’s not saying where. He adds: “I haven’t found any treasure yet, but I’m still looking!”

The treasure Nathan really seeks is higher water quality and a healthier environment. Cities that are full of hard surfaces that send rainwater shooting into local rivers, carrying sediment and pollutants with it, are not engineered for that. He and fellow city planners are re-imagining what “treading lightly” on the land means. Often it means renewed surface water with soft edges, wetlands, plenty of green space to slow rainwater down and hold it. And while Nathan doesn’t think it’s reasonable to resurrect every creek that has gone missing, he is hopeful: “Bringing water back, and celebrating it, is important.”

Dakota people on Lower Phalen Creek. Photo: Lower Phalen Creek Project

Upper Hidden Falls Creek is holding Nathan’s attention now.

Once a primary natural feature, Upper Hidden Falls Creek flowed through the land that is known in St. Paul as the Ford Site, near the Highland Park neighborhood. The 122-acre site sits on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi on the St Paul side, south of where Ford Parkway crosses the river. It was home to a Ford Motor Company manufacturing plant between 1925 and 2011. Now called Highland Bridge, it is under re-development for mixed housing, commercial sites, multi-modal transit, and ample green space for leisure and recreation.

Artist rendering of Highland Bridge development. Photo: Ryan Companies

Nathan characterizes the huge project as a major opportunity for St. Paul, and the region, to re-imagine water within the context of human habitation. “The Ford Company put the creek into a pipe for 80 years,” Nathan says. Environmental degradation was one consequence, but humans lost something in the transaction as well: “That part of St. Paul was completely disconnected from the Mississippi River because of that pipe.”

Historic Ford Motor Company plant in Highland Park. Photo: Ford Motor Company

Planners for the city of St. Paul, the Capitol Region Watershed District, Ryan Companies (the site’s primary developer), and contractors at Barr Engineering, like Nathan, realized that Upper Hidden Falls Creek could be the centerpiece of the new Highland Bridge community. Storm water management could happen, at least partially, at the surface and offer ecological, aesthetic, economic, and social advantages. The creek that once supported human activity could again be a focal point for the new neighborhood.

Water as a draw is not a new concept for St. Paul, or other cities: “You see benefits in all sorts of water. Mears Park,” Nathan offers as an example, “in downtown St. Paul has a FAKE, pumped-in stream. It’s fake! Yet people dangle their feet in it, children play in it, and it draws visitors, festivals to the park.”

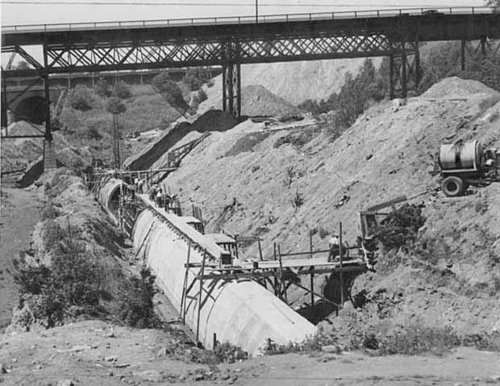

The place-defining water feature at Highland Bridge is taking shape. It is highly engineered, with concrete boundaries, filtration chambers, pumps, underground storage tanks, a re-created wetland, and a section of moving water conveyed under a road and bridge before it enters the Mississippi River, but it will bring back the feel of the water-that-once-was. It is described in planning documents as long and linear to give it a “river” feel, with areas of standing water to give it a “headwaters” feel.

Reviving Hidden Falls Creek in Highland Bridge development. Photo: Star Tribune

According to the Capitol Region Watershed District, the Highland Bridge water feature will capture and clean 64 million gallons of rainwater annually, preventing an estimated 55,000 pounds of suspended solids and 145 pounds of phosphorus from entering the Mississippi River each year. Designers have included access points for humans to touch the water and follow it on a bike or walking path along its journey from the neighborhood to a re-imagined Hidden Falls (at Montreal Avenue) and onto the Mississippi River.

Nathan beams with accomplishment. This integrated system of “green infrastructure” will help people reconnect with precious water: bringing birds, insects, invertebrates, blooming plants, beauty, and recreational opportunities to the new neighborhood. “Water protection is now the trend,” he says. “It is becoming baked into how we design and manage our cities.”

There is more work to be done, however, regarding broader public policy. “We are still putting too much storm water management underground,” Nathan says, and it’s important that discussions about a site’s water happen from the beginning of planning. He acknowledges, too, that water has social and political ramifications. “You can look at a map of the Twin Cities and you can see that communities that have been separated from water resources are the poorer communities.”

But politicians, planners and ordinary people are taking notice of water again. In his consulting work for cities and private developers alike, Nathan says, “We are being told, ‘Celebrate the water. Clean the water. Give us access to water.’” Citizens are more involved in keeping water central in their cities. “I’m lucky,” Nathan says, “to focus on the part of the project that everybody loves - water.”

Celebrating the daylighting of Lower Phalen Creek. Photo: Lower Phalen Creek Project

Resources:

Nathan Campeau: https://www.linkedin.com/in/nathan-campeau-6668b518a/

Barr Engineering: https://www.barr.com/

Highland Bridge / Ford Site Redevelopment: https://www.ryancompanies.com/project/highland-bridge-ford-site-redevelopment and https://highlandbridge.com/news/

Phalen Creek: https://saintpaulhistorical.com/items/show/291

Daylighting Lower Phalen Creek: https://www.lowerphalencreek.org/events

Photos: Tracy Nordstrom; Capitol Region Watershed District; Minnesota Historical Society, unless otherwise noted